Available in PDF

MY LIFE IN KAMPSVILLE

1919 to 1930

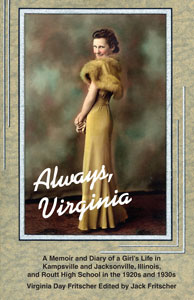

by Virginia Day Fritscher

hand-written September 1980, age 61

I was born July 12, 1919, on my Mom and Daddy’s eighth wedding anniversary, in this little town of about 200 population, named Kampsville, in Calhoun County, Illinois, the only county in the United States without a railroad. Most everything came in by boat and things were very expensive. In order to get out of the county, you had to cross the Illinois River by ferryboat or go to Hamburg, Illinois, where my Daddy was born and my parents lived the first few years of their married life, or cross by ferryboat over the Mississippi.

My mother was Mary Pearl Lawler Day, born in St. Louis, October 2, 1888–December 6, 1972. My father Bartholomew was born in Michael, Illinois, October 17, 1887–February 13, 1954. Because my mother’s former fiancee, Francis Devine, threatened he would kill her on her wedding day, my parents married in a secret ceremony in St. Louis in 1911 on July 12 which date in 1919 also became my birthday, and in 1938 my wedding anniversary.

In later years the State did build a bridge at Hardin, Illinois, about nine miles south of Kampsville, where one could cross the Illinois River, and which many times we and others would use as sometimes there was a little wait to get on the ferryboat because Kampsville was also a summer resort, with a lovely beach, cottages, and dance pavilion which was jammed in the summers I was a girl by people dancing the Charleston, come up from St. Louis and surrounding other little towns.

One of my first recollections of living in this little town was the back porch on the house we lived in (in the south end of town called Stringtown) on which my Mom would lift us up (no steps to porch), really a side porch and give us fresh, hot-baked roly-polies made out of pie-crust rolled up and sprinkled with cinnamon and sugar. Bake til golden brown. That’s the whole recipe. I also had a rabbit (a white pet—my very own) which I really do not remember, but my parents always told me about it as it would only come to me when called, but some mean older boys up the street killed it by throwing it by its legs in the air and letting it fall to the ground dead.

My next recollection was when I was three years old and we moved into our new home which my parents purchased—a big 8-room concrete block home—fenced-in yard—upstairs porch and front porch. It was the second house on the right from the main street. None of the streets had names. I remember trying to open the gate the day we purchased it and we all went up to look at it. I don’t remember the actual moving-in day but we spent many a happy day there until we moved when I was eleven to Jacksonville.

I had three brothers, John, Jimmie, and Harold, and one sister, Norine. My two older brothers, John and Jimmie, used to come into our room at night and run their hands up and down the wallpaper and make my sister and me think it was a bat, as once a bat did get in and we were a little apprehensive about being in that room, because my maternal grandmother [Honorah Anastasia McDonough-Lawler] died in that room when I was five years old. I always remember Grandma Lawler always had big round mints in her room with the Triple “XXX” on them and would give them to us. She took to her room when she was sixty years old, and never came down except to rock for three years until she died at age sixty-three.

Living in such a small town, I liked the woods which were only about two or three blocks away on what was called the Illinois River bluffs, and we always went there in the spring and picked wild flowers or just to hike. My brothers, John and Jimmie, went mushrooming, ginseng hunting (used to sell it to the local doctor), walnut gathering, and trapping possums. One morning when they went to check their traps before school, they had caught a skunk. Needless to say the smell did not get off their shoes before school and one of the nuns said to John, “John, you smell like skunk.” And he said, “You’ll get used to it, Sister.” John was my brother who became a priest. My Daddy and brothers always went coon, opossum, and etc. hunting at night and had a very good hunting dog. My brother Jimmie always made cornbread with bacon strips in it for the hunting dog. Jimmie who was the second oldest after John, see, turned out to be the owner and cook at Day’s Café, his famous little restaurant in Carrollton.

Daddy and John and Jimmie would put the skins of their animals on boards and dry them in the two big rooms we had upstairs that weren’t used for living quarters where we used to store a few bushels of good Calhoun apples and Christmas toys (which my brothers used to sneak in and play with before Christmas). They sold the animal skins. Daddy did have a fur made for my Mom and older sister, Norine, then and many years later one matching fox fur each for me, my Mom, and sister, and sisters-in-law, Mildred and Rosemary, but he didn’t hunt these latter foxes which he bought.

They also went squirrel hunting all the time (in season) and Daddy took me one day and we got five squirrels. You had to be very quiet in the woods so you wouldn’t scare them away. So Daddy had me stay back and he went a few yards further, but I was right behind him and he asked me “why” and I said, “Daddy, there’s a snake up there.” We had lots of snakes in Calhoun County and many times they were in our yard, because they’d come in on a wagon with the farmers. My Daddy, being a strict Irish Catholic, got a piece of some kind of tree limb, burned it, and with the ash part made a cross on our arm every St. Patrick’s Day to keep us from getting snake-bitten—an old Irish custom, based on St. Patrick driving all the snakes out of Ireland. My family besides being Catholic has always been Democrats.

I liked to work in the yard, and would surprise my Daddy and pull all the weeds or when he’d come home from his U.S. Rural Mail route, I’d proudly show him and be rewarded with a quarter, which was lots of money in those days [mid 1920s]. We used to get 15 cents every Saturday if we were good and get to go to the movie in Kampsville, which cost 10 cents, and spend the other nickel on goodies. My favorite movie stars were Bob Steele and Clara Bow, the “It Girl” of the 20s.

When I was smaller and the rest of the family, or rather part of the family, would go to the show, I’d stay home and be happy if they brought me a “load” of gum. That’s what I called a package as it was stacked like the loads of wood we would get many times a winter to burn in our Heatrola in the living room and cook stove in the kitchen. The boys had to keep the wood chopped and we girls would carry it in and put it in the woodbox behind the kitchen stove.

One day when my brother John, who was twelve or thirteen years old, was chopping wood, it was almost dusk and very cold. I was out watching him sitting in my swing and he kept telling me [age four or five] to go in as it was too cold, and I’d say “I’m rough and I’m tough, and I’m hard to bluff!” This would make him very angry, as he didn’t think it was too ladylike to begin with and was afraid it was, really, too cold.

On winter evenings we’d sit and watch the fire burn in the Heatrola and make out different images it projected on the little windows of the door. On Saturday night a tub of hot water was brought in and set to warm up by the Heatrola and there we’d take our baths. Saturday everyone shined shoes for church in the A.M. (I can still smell the shoe polish.)

One morning when I was five, my Mom and Daddy were getting ready to go to Church. I was in the kitchen and I cut off one of my curls. I disliked my curls as it hurt to have them twisted around a hot curling iron. And I threw the curl under the icebox, but Norine ratted on me. Mom couldn’t tell my curl was missing as I had so many, but I was reprimanded. Speaking of curls, I was never so glad or so proud to have them cut off by “Casey Jones,” our local barber. I was taken by my Daddy, and on the way home stopped by my Aunt Mag’s [Margaret Day-Stelbrink, my Daddy Bart’s only sister] to show her and my paternal grandmother [Mary Lynch-Day] who lived with her. They both cried as did my maternal grandmother [Honorah Anastasia McDonough-Lawler] when I got home and showed her. My, I was proud of my new “wind-blown bob,” and no more tangles.

My maternal grandmother, Grandma Lawler [Honorah], after whom Norine was named, died of a stroke at our home in April, 1924, when I was five years old and in first grade. I remember the neighbor coming over to our little school, which was just across the street, to get us. She remained unconscious for three days at our home because there was no hospital in this little town. I can always remember the death rattle for that period of time. My paternal grandmother, Grandma Mary Lynch Day died the next year in June, 1925, at age 80 years and 4 days. My maternal grandmother, Grandma Honorah McDonough Lawler, was 63. I believe my paternal grandmother had a stroke also. Grandma Lawler was buried in St. Louis and Grandma Day in Michael, Illinois, a town of about 25 where she was married and all her children baptized.

We used to go often to visit her grave and the grave of my grandfather, Bartholomew Day, born in Ireland, about 1824, who I never saw because he died in 1903 when my Daddy was a boy of sixteen. My Daddy’s father was much older than his mother, my grandma, Mary Lynch Day. My grandfather Bartholomew came from Ireland in 1868. When he was about forty years old and ready to marry around 1870, he traveled from Hamburg to St. Louis where he was introduced to Mary Lynch who was born at the start of the Potato Famine in 1844. She was from Waterford, was twenty years younger, and had a twin sister who, I think, stayed in Ireland.

Our only relative remaining in Kampsville was my Aunt Mag. Her husband, Uncle “Cap” (Casper Stelbrink), was twenty years older and very crabby, and they were quite wealthy. When I was twelve, Aunt Mag took care of us five when my Mom had to have gall-bladder surgery and went to the hospital in Jacksonville, Illinois, where she almost died. Daddy kept us at night. We had our school picnic while my Mom was in hospital. Usually we never ate often at my Aunt’s as we were five children in our family and they only had two—a boy and a girl, Joe and Cecilia, older than my oldest brother, John.

The Stelbrink boy was my cousin Joe, and on one occasion when our school visited Springfield, Illinois, to see Lincoln’s tomb and home, Joe was one of the drivers of the car I was riding in. Just for the excitement of it, I gave him a quarter to pass a car on the way home and he took it. That made my Daddy angry. Daddy made Joe give the quarter back to me the next day. Joe mellowed in his older years and married and had three or four children, but his sister Cecilia, never married.

We had to call Cecilia’s friends “Miss Josephine,” “Miss Mildred,” and “Miss Helen.” Those three were “the Kamps,” the oldest girls in the Kamp family, and sisters of my best friends who were the younger Kamp twins named Edna and Edwina Kamp, for whose grandfather our town was named. The Kamp girls’ father owned a grocery store in Kampsville and outside on one of the metal posts supporting the roof, one could get a small electric shock by holding onto it and twirling around. The Kamp twins and I did everything together—so much so that Sister Salvatore, one of the German nuns teaching at St. Anselm’s school, tied us together with rope one A.M.

Once, Sister Salvatore, who used to hit us with her pointer, said to me when I spilled ink all over my dress, “Oh, Virginia Day, you look like you fell in a sauerkraut barrel.” And Mom told me, “Virginia Day, you tell Sister Salvatore that only Germans fall in the sauerkraut.” Also at Christmastime, Santa visited at our Christmas program, and he gave me a stick. He must have been maybe a German nun dressed up like a German Santa, because that’s a German custom of giving coal and a stick to bad children. I cried, as, not being German, I was afraid my Irish Mom and Daddy would think I’d been bad in school as they were very strict, though kind and loving.

If we were sick, Daddy would come up to our room after supper and visit with us an hour or so. He was a US mail carrier and we always wanted to go with him on his rural route, but couldn’t unless he paid postage on us. That’s what he always said. On our birthday we girls, Norine and I, got to go once. The boys, my older brothers, John and Jimmie, were Daddy’s subs as was my cousin Joe, so they were allowed to go with him. It wasn’t a very long mail route, but in those days in bad weather, Daddy’d have to go by horse and buggy. We had two horses, Snip and Topsy.

There were many creeks that would swell when it rained and one day my Daddy and cousin Joe almost drowned when they were swept away in a red Model T Ford in one of the smaller creeks. I can remember Mom lighting candles at home and praying for Daddy as maybe it’d be 6 P.M. in bad weather when Daddy would get home. That night he got home much later, because it took awhile for his Model T to float into the trees and get caught so he and cousin Joe could climb out and save themselves. Sometimes he’d get home at 8 or 9 and would always leave before 7 A.M., go to post office, put up his mail, and leave. On good days he’d leave at 7 and maybe be home at noon. One day he had an unexpected piece of mail with him: my black bloomers. Mom and Norine and I searched the house for them before I went to school, and much to our surprise Daddy said he picked them up with some of his things. Norine said my bloomers got to go on the postal route before I did.

At Christmastime Daddy would come home like Santa Claus loaded down by his mail patrons with goodies like fresh country sausage and all good farm things like that. We had so much we shared them with the priest and sisters who lived in the St. Anselm rectory and convent across the street from us.

Speaking of the priest, he had a housekeeper who had a daughter my age named Elizabeth. One day I was engrossed playing ball out in front of my house and Elizabeth kept calling me. I told her I wasn’t coming over, but she kept begging me. So I picked up a rock, went over to the gate—I was about four, I believe—and said, “Come here, Eliz,” and hit her in the head with the rock. Needless to say, my Mom soon heard of it and I was punished. The worst punishment though was when I walked into Church the next day. Father Faller shook his finger at me. I thought, “Oh, he knows.” I was embarrassed. I never again hit a priest’s housekeeper’s daughter in the head with a rock.

I used to get into a few interesting wrestling matches and fights. One fight was with Kermit Suhling. “Kermie”did something I didn’t like, so I beat him up. My Mom kept saying at the door, “Shame on you, a little girl fighting a boy.” Well, Kermie gave me no trouble from then on. He lived in a beautiful home in the park, as I recall, where there were three homes owned by wealthy families. We were allowed to go to the park every night if we had behaved and we used to ride the “Ocean Wave” like a “Merry-Go-Round” that rocked. Our Daddy saw us and said, “Don’t ride the ‘Ocean Wave’ any more.” He was afraid we’d get hurt as big kids used to push it and get it going so fast. Well, about six weeks later we figured it was OK, but he saw us. He came over and got us and gave us a spanking then and there. We did not ride the “Ocean Wave” anymore.

One evening, Norine and I [six and three] decided to build a little fire under the front porch, because the boy next door (who wasn’t exactly normal) dared us to, but Daddy caught us and spanked us. We used to kid him in later years and say, “Daddy, we got punished just for trying to start a fire under the front porch.” There wasn’t a fire department in Kampsville.

We had a big swing on that front porch and used to enjoy many a happy hour there. I would swing my puppy and then he’d get sick. We had two dogs, one Jimmie’s hunting dog and one our pet and they both had pups at the same time and we had about sixteen dogs all at once. We kept the sassiest pup and named him “Teddy” and how he loved the woods. When I was eleven in 1930 and we moved from Kampsville to Jacksonville, we, of course, brought Teddy; but in Jacksonville we thought Teddy was dying of homesickness, so we gave him to people in the country, but he was back in our yard the next day. We never gave him away again. He liked us better than he liked the country. We liked that dog and his name. My sister Norine named her first child “Ted.”

My brother, Harold, the youngest of all five of us, got his big toe stuck in our high porch swing one afternoon. Mom tried and tried to get it out, but to no avail. When Daddy came home, he managed to free Harold’s toe. Harold also got scarlet fever and we were quarantined. Harold was named after one of Mom’s favorite writers she read and liked, Harold Bell Wright, who wrote The Shepherd of the Hills and The Winning of Barbara Worth. While Harold had scarlet fever, they boarded my brother Jimmie out across the street, but he got the flu, most likely homesickness, just like Teddy, and I can remember Daddy and the man across the street carrying him home. During the scarlet fever, we were in Harold’s room playing games every day, and none of the rest of us got scarlet fever though we all had every other childhood disease, I believe, at different times of course. Harold died at age fifty-five of a stroke while taking a shower. Rosemary said she heard him call out: “Oh, dear God, take me to heaven or get this pain out of my head.” (All three of my brothers died when they were 53, 54, and 55.)

In those days they quarantined you for everything. John was already away at school going to the seminary, so he didn’t come home during the quarantine period. He was studying to be a priest and my Mom said she heard three knocks on her bed one night and a voice saying, “I want John.” It scared her so she had Daddy call the school to see if he was OK and he was fine. Mom always believed that if your son had a calling for the priesthood, God would let you know and she always believed that the priesthood was John’s calling.

John made a wonderful priest til the day he died of a massive heart attack stepping into the shower to bathe before saying early Mass on April 9, 1967. Mom lived with him there in his rectory at St. Cabrini’s parish house in Springfield, and she held him in her arms on the bathroom floor. He was fifty-four; she was seventy-eight. [This incident is fictionalized in the short story, “Silent Mothers, Silent Sons,” in the book, Sweet Embraceable You: 8 Coffee-House Stories, by Jack Fritscher, published in May, 2000.]

John used to hitchhike home most every weekend as it was very safe then to do so. He’d write a letter home and draw a cup with the handle off with the caption, “Norine broke the last one.” And he’d draw a donut as a big hint so Mom would have fresh raised donuts when he came home. I don’t think I ever tasted any as good since.

My Mom was very ambitious for a girl who was raised in a house with an adoring father and four brothers named Jim, Ed, Jack, and Will who was a sleepwalker who once climbed a ladder up the outside of the house with a lighted coal lantern. Her mother, Honorah, made Mom do all the work. Mom said she herself used to stand on a little stool to make the bread, while her Daddy “carried her mother around in his hands,” as they used to say, because she always had headaches, and whenever there was an argument brewing, he’d put on his hat and go for a walk until the storm front had cleared.

I can always recall those long, hazy days of summer when she’d be canning twelve jars of everything for our family of seven and making lots of jelly. (I used to run around saying, “Seven Days! We’re a ‘week’ family!”) Daddy had two big lots where we grew a big garden as we raised most of our food. Oh, those strawberries! People would flock from St. Louis for a weekend in the country to enjoy Aunt Pearl’s delicious strawberry pie, Uncle Bart’s delicious sweet corn, potatoes, and cabbage, and to attend the dance at the beach. Just the way years later people flocked up from St. Louis to eat at my brother Jimmie’s famous Day’s Café in Carrollton.

My Mom used to have her wash on the line by 7 A.M., doing it on a washboard, have a big dinner cooked, and when we came home from school, she’d have something baked and be sitting at the window reading her Good Housekeeping magazine. Every evening she and Daddy would sit in the dining room and read, and we’d study in the kitchen, or when I was smaller, I’d lie on the floor and be intrigued with the rockers my Mom and Daddy were rocking on, and I’d get my hands closer and closer until I managed to get my fingers under the rocker. No wonder my fingers are crooked. My Grandma Lawler used to always sit in there too. The living room was reserved for guests and special occasions, though we had our piano in there and I took lessons and so did my sister from the banker’s wife. I did not like to practice and hated being called in from play to do so. The songs I played most were “The Fairy Queen Gavotte,” “The Fairy Queen Waltz,” and “The Bumble Bee.”

The piano was big, and I was little—like my mom, small for my age, until in high school I grew taller than my mom and sister—and there were little levers to raise the bench. One day as I was getting ready to practice, I just raised one lever and the bench tipped over. That did it. Mom thought I tipped over the bench on purpose, and she said she got the message, so I didn’t have to take piano lessons anymore. Anyhow I wanted to play the saxophone. Daddy said, “You’re so little, you couldn’t lift one.” I idealized the Foiles girls in town. One played the piano and one the saxophone, and I thought my sister and I could be like them. One of the Foiles girls was my 2nd and 3rd grade teacher, “Miss Grace.” I went to Catholic school in 1st grade, but 2nd, 3rd, and 4th to public as our town was so small we couldn’t get Sisters every year. I went to Catholic school, though, my 5th and 6th years. We always put on little school plays and I loved them.

I remember when we got electricity in the house. I recall the man saying it cost three cents everytime you turned the light on and off. Then we got our first electric radio, a Crosley named “Buddy Boy Crosley” that we used for many years, so we no longer used the battery set we had before that with headphones.

Kampsville, where tourists came for weekends, had many beautiful sights like the “locks” and the “flat rocks.” We would go out wading in the water very shallow, clear and cool, running over the flat rocks. When the river rose, part of the town was under water and the men would put up boardwalks. The water never came up as far as our house, but I can remember the spooky feeling walking on the boardwalks over the flood waters trying to get to Overjohn’s grocery or to Draper’s who had a dry goods store with a little restaurant where I’d order up a little ice cream cone which I always bought whenever my parents made ice-cream as I didn’t care for the home-made kind, because at Drapers, they would fill the cone with ice cream and then dip it in candy stars–which they didn’t do at home. What a treat!

There also was a store named Benninger’s. We would stop there on our way back to school and buy a penny’s worth of blackies, whities, brownies, or banana chews. We always had a few cents, because we would write Daddy a note at school and give it to him at noon, asking for a penny for the afternoon. All that candy led to some visits to the dentist who came up from St. Louis two or three times a week. He was Dr. Sweeney, and he made the amazing discovery that I had two sets of permanent teeth come in (just in front). I found out much later my teeth were just like my cousins Cecilia and Loretta Day who also had two sets of teeth come in just in front. I always claimed Dr. Sweeney pulled the wrong set, but he was far better than the old dentist we had there in Kampsville, because that old dentist, Dr. Holner, was alcoholic. We used to go visit Dr. Holner or rather the Tillisons, the people he boarded with, and I’d rock Dr. Holner’s dog to sleep while Mom and Daddy played cards with the Tillisons or just visited. I always loved dogs and was always bringing a stray home.

Mom belonged to the Women’s Club, a national organization, and when they’d meet at our house we kids would always laugh to hear them sing their opening song, “Illinois.” Very funny hearing them singing, “By the river gently flowing, Illinois.” The ladies played bridge and I knew from watching how to play bridge since I was seven years old, the way I learned pinochle from Daddy having his cronies in to play pinochle, and we’d be upstairs in our room, listening, and when they’d rap their knuckles down on the table while playing out a card, I always thought that’s why they called it “P. Knuckle.”

We also had good friends across the street by the name of Ruyles. Orland was my brother John’s age. Eustacia was my age. Their mother and father always called them “brother” and “sister.” So Orland and Eustacia called each other “brother” and “sister.” Like my Daddy, Mr. Ruyle was a Star Route mail carrier who had to move to Carrollton, Illinois, but they would come over lots of weekends to visit us. All of seven miles. One night when they were there my whole mouth and face was so swollen so Daddy took me to old Doc Woltman whose office looked like Doc’s in Gunsmoke, and he pounded on my teeth with a big nail and said, “It’s her teeth.” Next day Mom took me to the dentist and it was a boil inside my upper lip. The twins, Edna and Edwina Kamp, came over to see me next day and brought me a cupcake, but I wouldn’t let them see me, because I thought I looked like a monkey.

A Protestant church was right across the street from us, and we used to cut across there to go to the store and one day a hen with little chicks chased me and I’ve been scared of chickens ever since, but not Protestants. They called us “cat lickers” and we called them “pot lickers.” People don’t do that now.

Another thing we did in May, on May Day, May 1, was to make May baskets and bring them to the porches of people we liked. People who we disliked would get a string tied to their May basket, and then when they opened the door to pick it up, one of the older boys would pull the string. They used to do this a lot to a Mrs. Skeel, another doctor’s wife. Dr. Skeel was a good doctor, but was never sober, so no one went to him much.

We went fishing a lot, so we made our own poles. One day John and Jimmie were fishing and the town bully, Milo Pontero, began throwing rocks in the calm water. He wouldn’t stop so Jimmie, who was about twelve, got up to stretch, and Milo thought Jimmie was coming after him, so he threw a rock at him, and hit him in the head and Doctor Woltman said if it’d been a quarter inch closer to his brain it would have killed him. Jimmie won a bike selling the paper, The State Register, and I can always remember trying to get on it and ride it, but I was too small. I was so small, and a year ahead of myself in school, and I made my First Communion at St. Anselm’s when I was only five, because my brother John, who became a priest, took me to the pastor and told him I knew everything the six-year-olds knew. As a result, I graduated from high school when I was sixteen.

Another game we used to play in the yard was Mumbly Peg.

On midnight Christmas eve, we’d all be awakened and taken to Midnight Mass, but we couldn’t look at our toys before we went or when we came back. We had to wait until morning. One Christmas eve I remember my sister, Norine, saying she wanted a manicure set and it was there the next morning. We thought Santa had gone by the window when she said it. One year we got “Bye-Lo-Babies” made by Grace Story Putnam who copied off her own three-day-old baby. There’s a “Bye-Lo-Baby” in the museum at Springfield now. There weren’t too many made. Ours got broken. We should have ordered new heads for them.

We used to play movie stars a lot. We cut out pictures of them and then made them up to pretend they were going to parties. As I mentioned, there was one movie theater in Kampsville and the first movies I saw were silent. The first sound movie I saw was The Bridge of San Luis Rey, after my brother John came back from Jacksonville when I was nine or ten and told us at Jacksonville they had talking movies and you could hear them breathe. Some years later, I got some horse hair from the tail of Tom Mix’s movie-star horse when he was at the fair in Jacksonville. I just walked in and asked if I could clip some souvenir hair and they let me.

From my money I earned when I was fourteen selling hosiery, I also spent 75 cents and took a ride by myself with a pilot in a little plane called “Big Ben.” My brothers told me not to go because it might crash. It wasn’t much of a thrill, and I was so disappointed, but it was nice to be the first one we knew to take off in Jacksonville and fly twenty miles to circle the view down all over Kampsville, Carrollton, and Eldred to see where I came from.

Before a storm, I can remember we used to always run like crazy around the house. Mom burned palm from Palm Sunday to make the storm stop. She’d stand outside the door on the porch lighting the braided palm and sticking her arm out into the rain, shaking off the ash, which made us all feel better. The yard seemed so big then, and decorated beautifully with Daddy’s big, blooming, red cannas, but when I went back in 1968, the yard seemed so small.

On occasion I would go over and spend the day with my Aunt Mag and help her churn butter.

* * * *

This is amusing to say, as I just had the chance to visit my old home September 6 and 7, 1980. It’s now on the map. Really! There is an article from the Wall Street Journal this very week reporting all the archaeological digging that started in Kampsville a few years back. I noticed in our Peoria paper a Kampsville trip sponsored by Lakeview Museum in conjunction with the museum’s exhibitions, “The Rise of Life at Koster.” Until recently, Koster was a cornfield I once played in, and now it’s the oldest site of civilization in America, dating back centuries before Christ to 9500 B.C. The trip included a tour of the Ansell Site, which was on my Daddy’s old rural mail route. The archeology laboratories are located in the old post office that my Daddy worked out of and in which my cousin, Cecilia Stelbrink, worked as postmistress, I think, for thirty-six years.

I went down Friday at 5:45, September 6, with a group from Lakeview. We crossed the Illinois River by ferry that Friday night, and crossed over to Kampsville from Greene County. Many on the tour had never ridden a ferry before. Now it’s operated free, but when I lived there in the 1920s, it cost 50 cents each way and took so long. For the ten minutes it now takes we all got out of the vans and stood in the ferry. There was a huge barge coming down the river, the longest one I ever saw. We were standing so close to the gate of the ferry that water splashed up on us. I left the tour and stayed all night with my cousin, Cecilia. We sat up and talked until 2 A.M. We got up at 6 so we could eat breakfast and go visit the new Catholic Church which was built in 1978. The Church I had attended was 100 years old that year. They have a history book of the Church and the town.

We walked all around town, past my old house, which still looks lovely, although the current owners have knocked out the ceiling of the two rooms, the living room and bedroom, and made a cathedral ceiling and a huge fireplace. Cecilia said an “Arkie” lives there. I asked her who were the “Arkies.” I thought maybe the word she was saying meant they were people from Arkansas, but the archaeologists are known as the “Arkies.” We went by Cecilia’s old house, and Kamp’s old grocery store which is now a closed-down clothing store. Kampsville has only one grocery store now and used to have four at least. We walked by my Daddy’s old garden lots. The house built on them by my doomed cousin, Loretta Day, and her dentist-husband, Phil Ritter, is still there, and the new bank and new post office are next to them.

That early morning was quite foggy. I didn’t remember all that fog when I was little, but guess I was used to it. Our tour started at 8:30, so Cecilia brought me to the Kampsville Inn, where I met the rest of the tour who had stayed overnight at the Inn or dorms the Arkies own and operate. Cecilia and I met for lunch and several from the tour ate with us. All this is being done by Northwestern University, and Kampsville is the oldest spot in the United States where they are digging for these artifacts of the Havana Hopewell Indians in six mounds where they’ve found 150 skeletons and pearls from the Illinois River, and figurines of men and women and ravens with pearl eyes, and pipes, and arrowheads like we used to find just accidentally walking around.

Also, I remember from the 1920s up as late as the 1940s and 1950s, people used to open Indian mounds as a roadside attraction where for five cents you could go in for the educational experience of seeing broken pottery and skeletons of whole families lying on display in the dust where they found them. People can’t do that anymore either. All this archeology started because some man—I think named Gregory Perino—came by Pearl, Illinois, where Perrin Ledge is, and he saw all these old Indian mounds and burial grounds and decided to start digging in Kampsville and thereabouts in Eldred. There is a legend that a man named Gerald Perrin jumped from that ledge, and so this rock got its name. There’s a big blue house and the ledge is behind it, and why Gerald Perrin jumped, my Daddy joked, nobody could ask him.

On Saturday morning, we all went to the lab site where the Arkies showed slides about how they found and packaged everything they found and sifted. They explained how they dug everything up. We were also supposed to go to the Audrey Site back across the river, but it was too wet. They had the site we went to all covered with tarps as they’d had heavy rains the night before we arrived, as well as the morning of the day we arrived.

After lunch we went back to the labs, to other rooms, where we were shown a flint-napping demonstration. The Arkie showed us how the Indians made their arrowheads. We used to find them in the woods when I was a little girl and sell them to the local doctor. The Arkie demonstrated how to make an arrowhead and he gave it to me and let me keep it. Everyone on the tour thought it was so neat that I was born there and lived there the first eleven years of my life, and I’m the same person now I was then, though not eleven, and more progressive than some in Kampsville were back then when boys (not my brothers) would throw rocks at any blacks—who worked on the boats delivering goods—if they tried to get off the boats and come into town. Awful.

All of us on the tour later went to what they had turned into a museum, but to me was still the old local butcher shop where I remember always being given a weiner by the butcher, Polly Rice. I remember going down there on afternoons in the summer and getting cold Nehi soda, especially grape, orange, and strawberry. The lady who was in charge of the museum was named Marguerite Becker. Her maiden name was Schumann, and she and her family had lived on my Daddy’s mail route. She said how much respect they all had for our family and for Daddy as a mail carrier and for Mom who was so sweet.

One of the archaeologists who was with us most of the time was Lisanne Traxler, and she said if I ever write a book about Kampsville, she wants a copy of it. The Arkies have forty-two sites in the Kampsville area where they are digging. Students from different schools come in and help them in the summer.

The last place we visited was behind the museums which was the backyard of the old doctor’s house. The Arkies had built many little primitive huts like the people built in that era before we all came along. In fact, the Arkies were demonstrating building one of the huts out of cattails and mud.

At the end, we all walked back to Kampsville Inn and got in our cars, crossed the ferry, and headed back to Peoria. We stopped at Jacksonville to get gas, almost 45 miles from Kampsville. In Jacksonville, I spent my next 10 years, from eleven to twenty-one (April 1941), and was married there and gave birth to Jack at Our Saviour’s Hospital in 1939. Then we stopped in Virginia to eat dinner—a marvelous restaurant for a small town—that attracted people from all around, the way my brother Jimmie’s “Day’s Café” in Carrollton attracted people from all over in the 1950s. While we were in the restaurant, a terrible rain storm, with wind that turned into the usual tornado came up. The lights went out three times and rain was gushing down the plate-glass windows. It was like someone was sloshing buckets of water on them. We needed my Mom throwing burning palm out into the storm. By the time we finished eating and went to our van to resume our trip back to Peoria, the storm was all over but for the usual destruction for southern Illinois. We drove past uprooted trees, branches, and debris across the highway. The cornfields leveled. We arrived in Peoria safe and sound after a most interesting and enlightening weekend about 10 P.M.

Going to many of the sites in Kampsville brought back many memories. The new people in Kampsville have fairly much buried most of the old ways the people I knew lived with, like we’re one of the old tribes that once lived on the site. They’ve graded most of the hills now, and filled in the creek, and paved the roads, and named the streets. I remember those hills. When I was small, we used to go uphill to Hamburg to visit my Grandma Day and uncles and aunts and cousins. We’d push with our hands and feet on the back of the front seat as Daddy went up the hills, because cars were new to everybody and we thought pushing on the seat was helping the old Model T to climb.

Our main entertainment was going to visit relatives or them coming to see us. Two of my daddy’s brothers married sisters [John Day married Addie and Joseph Day married Ella] and their children always let us know they were a dozen times more related to each other than to us. They never started school till 5th grade, because both their mothers were schoolteachers and taught them at home. They called their parents “The Folks,” and when they’d come over unexpectedly some Sunday afternoon, they’d tell us kids that “The Folks” were planning on staying for supper, so we’d tell Mom and she’d have us run down to the store and get some choice cold cuts, etc. as we had eaten our big dinner of roast, or chicken, at noon, and, needless to say, after feeding seven, there wasn’t enough left for four more, no matter how many dozen times they were related to each other.

My uncle John Day, who also lived in Hamburg was the judge of Calhoun County. They both, Uncle John and Uncle Joe, ran huge apple orchards. Uncle John’s son, John W. Day, is now a judge in Granite City, Illinois. Uncle John’s daughter, my cousin, the doomed Loretta Day, used to come and stay a week at a time with us, so that her fiancee Phil, the dentist, could visit her at our house. Loretta had a signal set up with my Mom to call down at a certain time when Loretta wanted Phil to leave at night. Loretta married Phil, but she died of pneumonia when she was seven months pregnant. What’s sadder than a dead bride? Later, Raymond Draper accidentally ran Phil over, and Phil had to have a metal plate put in his head.

On occasional weekends we’d also drive over to Carrollton, Illinois, to visit the Ruyles I mentioned earlier, the family with the brother and sister, Orland and Eustacia, who moved from Kampsville to Carrollton, and they’d also come visit us. Eustacia, “Sister,” and I when we were quite young decided to mow the lawn. Eustacia was smart enough to push at the handle. Dumb tomboy me pushed at the blades, and a little cut finger taught me a lesson about where to push.

Those weekends we had to drive back to Kampsville by Monday so Daddy got back for his mail route and us kids for school and my Mom for the housework. When Daddy would get home early in nice weather after dinner, which we ate at noon, we’d all go in, all five of us kids, and lie down with him on the floor with all our heads on one pillow, and Mom said it looked like the spokes of a wagon wheel. It was very hot and no such thing as even a fan on those days, and we couldn’t go out and play right after noon, so we got to lay around with Daddy, until Daddy would go to the post office about 2 P.M. and put up the mail for the next day.

When I was eleven years old in 1930, my parents decided to move to Jacksonville as my brother John was already going to school there at Routt High School and College, and my brother Jimmie was ready for his senior year. Kampsville had only a three-year high school. My Mom and Daddy thought it’d be cheaper to move there than send all five kids away, because my older sister, Norine, was ready to start high school. Daddy transferred up there to that post office, but his transfer didn’t go through right away, so he stayed in Kampsville that whole summer and I stayed with him while the whole rest of the family moved on to Jacksonville.

He and I used an upstairs room in the house we had owned, but just sold. We ate our meals out at my Aunt Mag’s—except breakfast. Everyday Daddy gave me Post Toasties for breakfast. To this day I can’t eat a Post Toastie. I used to kid him about it when I got older, but he denied giving them to me every morning. We always made quite a joke of it. I loved staying with him. I got to spend time with my friends, the Kamp twins, every day, and got lots of individual attention from my Daddy and Aunt Mag and cousin, Cecilia. That summer I used to help my Aunt Mag churn butter. She loved to have me help her as her arms would get tired, and I felt so big doing it. I always had my little purse full of spending coins that she and Daddy would give me. In afternoons the twins and I would take walks and go to the local drug store and sundries shop and have a Coke.

Daddy and I would drive home to Jacksonville every weekend in his little Model T open-touring Ford truck. We’d bring lots of vegetables and fruit from Daddy’s lots with us. In the fall, Daddy’s transfer was final, so before I started back to school, at a new school in Jacksonville, he started back to work in the Jacksonville post office.

Halloween is coming up soon now and it makes me think of the Halloweens back in Kampsville. The morning after Halloween, outhouses were all pushed over, some, or at least one, I remember, was put up on a telephone pole on the main street across from the Kamp’s store. When my sister and I had to go to the outhouse on Halloween, my brothers would sneak out and bang on the walls and make us think we were going to be tipped over. We were allowed out with our real carved pumpkin jack-o-lanterns that we made and put a candle in, and we would walk up and hold them in people’s windows for them to see after we knocked at their door. There was no such thing as trick or treat. Just tricks! And my older brothers weren’t allowed out after they outgrew the jack-o-lantern trip, as there was too much vandalism or maybe just devilment, and the local constable, whose name was Bennett, would make a few arrests if he found any culprits, and my Mom and Daddy didn’t want our family blamed.

We had another friend we visited frequently in Hamburg. Her name was “Mag Kelly,” a very dear old friend of my mother, and we always called her “Aunt Mag” even though she wasn’t a relative like our real Aunt Mag who lived in Kampsville, and was the only aunt we had by blood. In this very big interesting house, filled with beautiful antiques, lived Aunt Mag Kelly with her sister, Annie—and Annie’s husband, Tom—and her sister “Doty” Kelly who was a little slow, as well as her sister Kate Kelly who lived there occasionally, but worked in Staunton, Illinois, and in later days finally moved in full-time with Aunt Mag Kelly. Kate Kelly always told us Santa Claus lived in Staunton, and we believed her. None of those Kelly sisters had ever married, except for Annie who married Tom.

When we’d go over for supper at Aunt Mag Kelly’s on Sunday, she’d send us on a wonderful little errand. We’d cross the road, go up a steep hill, and to the Spring House, which was a big wooden box built over where ice-cold water seeped slowly out of the ground. That’s where Aunt Mag Kelly kept her butter, cream, etc. The spring itself and the Spring House were delightful. I don’t know what happened to Aunt Mag Kelly’s house or furnishings after they all died, but the antiques she had in there would be worth a fortune. I always remember the big picture she had in the living room of horses running in a storm. It always intrigued me. Aunt Mag Kelly lived, I’m sure, until after my older son, Jack, was about three in 1942, when my younger son, Bob, was born. I guess none of them at Aunt Mag Kelly’s had a will and she was last to go, and everything just vanished, probably still floating around in flea markets. Nobody I knew seemed to know.

There was also a man and lady we visited named Frank and Maude Rohl. Frank was also a mail carrier. They had no children, but I always remember they had a lawn swing we’d always swing in when we visited them. They had a beautiful back yard, grape arbor and all. I don’t believe the Rohls were related to us. If they were, it was way back, and they could have been, because we had Irish relations, and shirt-tail relations, around St. Louis back since about 1849 when my granduncle [John Day] first arrived from Ireland, which was about the same time when my maternal grandparents’ parents—both sets [Lawlers and McDonoughs]—came from Ireland themselves. Cecilia knew about the Rohls, but I lost track.

In Kampsville, the cemetery was up on the hill with a long, winding road going to it and we always went sleigh-riding down the cemetery road every winter, which my little brother, Harold, said was convenient if we insisted on killing ourselves. I remember one winter when it snowed real deep and then sleeted, and our back yard turned to a sheet of ice. That one night while Mom and Daddy were reading in our dining room, we snuck out and played sleigh-ride right on top of the crust of snow. There was a creek right behind us and when it’d freeze over, the boys would ice skate on it. We had little 4-runner skates and we girls would skate on it too.

When it rained, winter or summer, that little creek would rise up in a raging current almost to our back fence and we’d throw our tin cans in and watch them float away. Daddy always warned us away from water of any kind. He said drowning ran in our family, but I don’t know of any relative who drowned except his mother’s father, Jack Lynch, who was a sailor. So I guess he was trying to scare us into being safe. Actually, Daddy himself nearly drowned when his Model T was swept away full of mail.

On the river at Kampsville, we also had “locks” that raised and lowered the water level for boats. The locks were very beautiful with lovely landscaping around them where there were three or four homes where the locks-keeper and some of the other employees lived. I went down there to a party at one of the homes one Saturday. We’d all often go there for picnics and fishing. Mr. Nordbusch, who ran the locks, kept his family there. He had two boys and the older one, Norbert Nordbusch, was very, very stuffy. When my oldest brother, John, came home from Routt High School in Jacksonville, that stuffy boy Norbert strutted out to meet him and said, “Well, Johnny, did you ‘paaass’ in everything.” It was always a rather standing joke we made on each other. “Did you ‘paaass’ in everything?” In the church history book the present priest interviews Mrs. Nordbusch who is now in her 90th year. The Nordbusch’s finally moved to Peoria for Mr. Nordbusch to take care of the locks during the War in the 1940s.

I don’t want to forget one of the highlights of my first eleven years was shaking hands with Governor Len Small, then the governor of Illinois. We were attending a centennial in Hardin and I walked right up to the Governor and shook his hand. Speaking of Hardin, they had a bad cyclone there when I was about nine, and we went down to view the destruction. A piano was hurled out of a home and hanging on an electric wire. I always seemed to be involved in weather—like dust storms so thick coming home from school that in those years we started washing our hair every day.

We had chatauquas with vaudeville acts and concerts and speeches in Kampsville. One time a ventriloquist came to town and his little dummy kept mentioning names of people in the town, and we couldn’t figure out how he knew them all, and made such a joke. The chatauquas were held in a big tent set up in the vacant lots across from my Aunt Mag’s [Day-Stelbrink] house.

What is the Kampsville Inn now where some of our party stayed in 1980 (used to be a hotel as I mentioned before), but one side of it was a grocery store owned by people the name of Hartman and their daughter, Theresa, who for some reason was crazy about bridge tally score cards and I’d always sell her all the cards I collected from the tables of ladies after Mom had one of Kampsville’s famous continuing bridge parties at our house, or went to one and brought me the cards. Theresa paid me from two to five cents each and I used the money for fun. I assume Theresa could have purchased the tally cards herself somewhere in town. Her parents’ grocery store could have carried them, but I was delighted she wanted mine. She was in my class at school, and she always had money and candy from the store.

I also had a classmate named Harold Kamp, cousin to the twins, whose father was killed and he was the only boy, and his mother had quite a time with him, as he used to eat pencil shavings and drink ink to show off at school. I believe Cecilia said he’s still living. Must have been permanent ink. Of course, I thought eating pencil shavings and drinking ink would kill him, because my brother John told me he was going to call the undertaker when I told him I swallowed tooth paste while brushing my teeth one night and asked him if it’d hurt me.

I think this pretty much sums up my first eleven years I spent in Kampsville, My cousin, Cecilia did tell me, as I mentioned earlier, that when I was down there this September that she and my cousin Loretta Day had two sets of teeth, as I had. Cecilia said when she was little, she was afraid to go to the dentist and her mother shamed her and said, “Virginia Claire Day went alone.” She told her mother then she’d go, but wouldn’t let the dentist do anything. So I guess she went through life with two sets of permanent of teeth, whatever that means. We grew up with lots of folklore, like believing if you wore rubber galoshes or boots in the house or school, you’d get sore eyes. I guess they told us that so we’d take them off when we came indoors. Back then people told a lot of stories with lessons attached, like my Daddy’s drowning story.

I enjoyed my first eleven years at Kampsville, growing up in a real small, woodsy town.

Cecilia called after I got back and said that “Kermie” who’s still alive, said he was sorry he missed seeing me.