Cruising – The Movie

THE GAY CIVIL WAR

WHEN THE BOYS IN THE BAND

ATTACKED THE LEATHERMEN IN CRUISING

by Jack Fritscher, PhD

Any film fans seeking a backstory about the wild 1970s? When leathermen cruising out on motorcycles wanted to be seen? When Stonewall unity fractured into a gay civil war of hostility over virility? When sweaterfolk attacked leatherfolk? In John Ford’s 1962 film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, a news reporter says, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

The queer uprising censoring William Friedkin’s Cruising may be legend, but history seeks facts. Context is everything because the Titanic 1970s, that foundational decade after Stonewall, so glorious before the iceberg of AIDS, was itself legendary.

As with diverse Stonewall myths cooked up by Manhattan journalists around the core of the June 1969 rebellion itself, there are many Rashomon sides to every story, and every story like every film needs a focus puller and a script supervisor to make sure scenes make sense in the final cut.

The shameful 1979 street censorship of Cruising led by Village Voice crime reporter Arthur Bell began four years earlier in July 1975 when Village Voice reporter Richard Goldstein writing “S&M: The Dark Side of Gay Liberation” assailed the quintessential leather artist Rex (1944-2024), blind-siding his gay gaze, calling him a Naziphile, and condemning his leather-fetish drawings. The alleged hatchet job was a declaration of war on leather culture, and a queen’s gambit to erase masculine-identified leathermen.

Rex, who in 1976 became the official artist of the Mineshaft, the bar dramatized in Cruising, said of the four years of this Queer Inquisition that turned difference into division: “Censorship is a desecration of the artist’s idea.”

In the civil war over “proper” representation of gay male gender, Rex along with his frenemy, leatherman Robert Mapplethorpe, are 1970s avatars on which to investigate the toxic masculinity of Arthur Bell, the wannabe influencer who when William Friedkin began shooting Cruising on July 2, 1979, freaked out in the July 16 Village Voice over the Hollywood director’s documentation of a night in the life of leathermen.

When Friedkin refused to pay him attention, Bell turned vengeful Pied Piper leading representative ticket-buyers away in a punitive pride parade that became a curious action sequence in the final cut of the “Big 70s Movie” of the way we were.

The leathersex reality we lived back in that day was a real-time Fellini-Visconti Roman orgy whose local black-and-blue color Friedkin wanted to invoke in Cruising as part of his series of movies reflecting East Coast life in New York and Washington: The Boys in the Band, The French Connection, and The Exorcist.

Arthur Bell, who had read only a stolen first draft of the shooting script, jumped to conclusions and set out to cancel rather than help improve Cruising because the gay saboteur had a grudge against the straight auteur. Follow the money. Bell thought the Oscar-winning director was basing his shooting script less on New York Times reporter Gerald Walker’s 1970 novel Cruising and more on Bell’s true-crime columns without crediting Bell or paying him.

Hell hath no fury.

Like a Mob Boss, Bell bragged he “put out a contract on the movie.” He wrote: “Give Friedkin and his production crew a terrible time if you spot them in your neighborhood.”

If Bell, a thirsty journalist who made himself part of his stories, hadn’t insisted on selling “Trouble” like Harold Hill in The Music Man, he could have changed history by meeting with Friedkin to counsel him about his straight gaze the way the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) would deal with media after its founding in 1985, a year after Bell died from diabetes. Instead, Bell went viral infecting the psyche of the national gay press reviewing Cruising.

Bell accidentally gave Friedkin a million bucks of free publicity for a modest genre movie that might have been better boxoffice if the straight Friedkin, a fan of Godard, had forsaken Technicolor for hand-held black-and-white stock and hired an insider like Rex to create the art design, costumes, and storyboards whose fisticuffs Robert Mapplethorpe could have lit and shot as film noir.

After all, Rex, himself an incarnation of his leatherman drawings, created the international marketing art for the Mineshaft as a leather habitat for all its nine years and nine days from 1976-1985. In 1982, Rainer Werner Fassbinder knew the value of making leather heritage seen when he designed Jean Genet’s Querelle on the drawings of Tom of Finland and scored an art-house hit.

Even so, Friedkin’s noisy bacchanale completed a jazzy “Leather Visibility Quintet” with Brando’s The Wild One (1953) Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1963), Fred Halsted’s L.A. Plays Itself (permanent collection at MOMA, 1972), and Roger Earl’s Born to Raise Hell (1975).

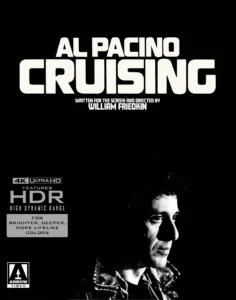

Drummer, the gay men’s adventure magazine of leathersex, art, and culture from 1975-1999, accepted Cruising as the then best cinema vérité take on the real 1970s leather subculture of homomasculine men in a Hollywood film. With Pacino’s nuanced masculinity, Cruising was 102 minutes of the joys, obsessions, and risks of leathersex sans regret.

Because Cruising was released on February 15, 1980, and AIDS hit the fan on June 5, 1981, Friedkin was twice cursed when 1980s critics retrofitted his film as if it were prosecutorial proof that Black Leather caused the new Black Death. When gayfolk building on Bell’s book and scandal clucked out the bias of hindsight that leathermen didn’t know what was lurking around the corner, well, who does? The 1970s didn’t cause AIDS. A virus caused AIDS.

Did Bell, despite studies to the contrary, really believe that violence on screen causes violence in the streets?

In his own apartheid, Bell said nothing about the damaging image of straight women cruising New York nightclubs for dangerous hookups in the 1977 homicidal film Looking for Mr. Goodbar starring Richard Gere whom Friedkin had wanted to play the Pacino role in Cruising.

Bell who watched Divine eating dog feces in Pink Flamingos in 1972 was worried about the image of gays in Cruising?

While vanilla gays confused consensual S&M leather action with non-consensual violence, the politically-correct anger at Cruising was also pent-up anger at the Mineshaft for its “fascist” dress code of October 1, 1976, that, protecting its sanctuary of leathermen in a campy decade of invasive Judy-Bette-Barbra drag, excluded “cologne, perfume, designer sweaters, tuxedos, and disco drag.” It was easier to get into Studio 54 than the Mineshaft.

Did Bell’s dog whistle bring out opportunistic camp followers nostalgic for the Stonewall riot they’d missed ten years before? Like American Civil War re-enactors, did they fancy acting out a new Stonewall moment starring themselves?

Bell himself was a stock character in a comedy of manners. His street theater was like the flaming cast of Boys in the Band attacking the cool leathermen in Cruising when, in fact, if the rebellious enjoyed being pissed off, they should have attacked Friedkin years earlier for his decadent stereotypes of gay men in Boys.

Bell and his henchman Vito Russo, the troubled author of The Celluloid Closet, impugned the draft shooting script, trying to cancel the creative process of director, cast, and crew whose art-in-progress vision they were disrupting with no idea of the holistic final cut.

Bell’s rage was a fundamentalist failure of critical thinking crushed by gay politics. Even Mexican-American author John Rechy, no lover of leather, spoke out against Bell’s “prior censorship.” Rechy, whose novel City of Night had been attacked exactly like Cruising in 1963 for images of manly men cruising the night, conferred creatively with Friedkin and suggested small changes for the final cut.

The segregation of leather culture and the censorship of Rex and Cruising are the same apartheid that set the stage for the more famous censorship of Robert Mapplethorpe’s leathery Mineshaft images denounced by bellicose Republican Senator Jesse Helms on the floor of the U.S. Senate in 1989.

To date, many Talking Heads on page and screen continue to push Bell’s partisan legend as the only POV despite testimony from eyewitness survivors of that Titanic decade. Shouldn’t research include new scholarship? How fresh the point and counterpoint if the director of The Exorcist had a Devil’s Advocate.

Bellistas ignore the inconvenient truth that the thousands of leathermen who read international Drummer magazine welcomed Cruising as a documentary about living a life eyes wide open in leather. Drummer helped create the very leather culture it reported on. More people have read the 22,000 pages of erotic inquiry in the 214 monthly issues of Drummer than have read Arthur Bell or viewed Cruising. As editor-in-chief, I reckoned Cruising included all the elements of the S&M stories readers of our 42,000 monthly copies loved.

When Friedkin’s leather-freighted Black muscle cop, nude but for boots, jockstrap, and cowboy hat, enters the interrogation room and slaps Pacino hard across the face, knocking him to the floor, it was such stuff as popper-dreams are made on. That inter-racial slap, as meme and trope, taboo and totem, thrilled Robert Mapplethorpe, the official photographer of the Mineshaft. A production still of that “cop slap” rang so true to leather psychodrama that it could have been a hot Drummer cover. Perhaps Friedkin sourced hands-on slaphappy inspiration in Tennessee Williams’ canonical S&M story “Desire and the Black Masseur.”

Twenty-first-century folk searching into the authentic erotic “feel” of Leather La-Dolce-Vita in the 1970s, a gestational decade in the long history of gay identity, will witness in Cruising the authentic pop-sex world that Rex made seen in hardcore fetish art and Mapplethorpe, turning Dionysian life into Apollonian art, presented for museum consumption. To wither recalcitrants like Bell, Mapplethorpe said: “If you don’t like this picture, maybe you’re not as avant-garde as you think.”

Cruising was so favored as a “home movie” featuring dozens of Mineshaft regulars as extras eager to be seen that Wally Wallace told me it was the first 16mm movie he allowed to be screened in the Mineshaft.

Bell was a Puritan misandrist handing out Scarlet Letters to Cavalier men for sinning against permissible degrees of gay masculinity on the Kinsey Scale. His attack on Cruising was in reality a scapegoat attack on the first wave of 1970s homomasculine men coming out in virilizing venues like the Mineshaft, in Drummer, and in the art of Rex, Mapplethorpe, and Tom of Finland.

Bell’s crusade was only one battle in the 1970s gay civil war waged on both Coasts against leather culture led by Richard Goldstein at the Village Voice and Los Angeles publisher David Goodstein at The Advocate who editorialized that only proper men in suits and women in dresses, not leather freaks, should show up for demonstrations, pride marches, and TV talk shows. Unlike Drummer re-wilding masculinity without separatism, the two newspapers trashing Cruising wanted to control and tame the media image of gayfolk so they would not alienate advertisers not wanting to pay for liquor ads next to dildo ads.

In a 1978 tale of two cities, Arthur Bell’s erstwhile lover, Arthur Evans, an evangelical gender missionary of gay faerie, who was also obsessed with Nazis, moved from Manhattan to bedevil masculine guys in San Francisco. The anti-patriarchal Evans failed to understand the community gender roles of nurturing Leather Daddies when he posted his essay “Afraid You’re Not Butch Enough?” on Castro Street lamp posts.

Mere days after Harvey Milk was murdered, I made sport of Evans aka the “Red Queen” in Drummer 25, December 1978. Fourteen months later, Cruising opened like a dreamy Drummer movie, a cautionary tale of beauty and terror helping leathermen deal with desire and danger because the renewable energy of erotica is the best panacea for gays wounded by homophobia.

Bell’s 1979 censorship doubled the PTSD Rex suffered from the Village Voice in 1975 and drove the consummate New Yorker to escape like Harvey Milk from the gated cliques of Manhattan to the open city of San Francisco. Like his peer, physique photographer Jim French of the leathery ultra-masculine Colt Studio, Rex exited New York to open his second act to new West Coast vibes while both he and Mapplethorpe found patronage through international Drummer in San Francisco where leathermen took Cruising in stride, not as stigma, but as date movie.