“This story is about me.”

— Robert Mapplethorpe

Caro Ricardo

Ricardo Rosenbloom arrived unlikely in my life. Everyone else I ever met needed money, time, encouragement. Ricardo was an adult. His “take” on my life was real and realistic. He pleased me: he was a grownup, superbly accomplished, and appealing to me who had for one-more-time declared my Finishing School for Wayward Boys recently and permanently closed. I had had enough of gayboys who wanted to write but never wrote, who wanted to shoot photographs but spent their cash on coke not cameras, who wanted to sing but never sang.

So here was Ricardo perched brilliantly at the start of a great career. His photography had shot beyond the Manhattan novelty of a new talent in SOHO. The right people sat in Ricardo’s studio. The right runs of photographs, dispensed in limited editions, found their way into the right galleries, the right magazines, the right addresses. Vogue phoned to ask him to shoot whomever he thought hottest for its pages. We mused over Faye and Fonda, Gere and Travolta. We laughed about names with faces to be shot before they faded. We discovered we had virtually the same values. We shared a taste for money and celebrity. We liked the people behind both. Our talk unraveled in shops on Greenwich where we absently browsed antiques. Ricardo was an offhand collector. He wrote impulsive, enormous, and canny checks for small bronze sculptures of the goat-footed devil.

“Nineteenth-century British,” he said hoisting his shopping bag. We walked like two improbable Bag Ladies down Christopher Street to Sheridan Square. Ricardo carried the bronzes in one smaller bag filled with black magic candles and sex magazines. I toted one larger bag, heavy with new, black, rubber hip boots from Stompers. We were ripped and happy with my brief visit with him in New York.

Suddenly he stopped our progress and reached first into his bag and then mine until convinced he had in fact lost in the last restaurant the current Rolling Stone with the review of punk-rocker Conni Cosmique’s new album “The Luxury of Mental Illness.” Conni was Ricardo’s friend, his former roommate, and the subject of his current video, Conni Cosmique and the Comettes. Stoned on MDA, Conni had let Ricardo search her considerable soul with his RCA-007 color camera. He wanted me to view the tape, but all our lingering in Village cafes somehow left no time to see the raw footage. He seemed a little hurt that we couldn’t share his work in progress. One of those moments passed between us when one can’t do what the other wishes. “Too bad Conni’s not in town,” he said, vaguely implying I’d regret it forever.

I figured if Ricardo liked Conni, lived with her when he was fresh out of Pratt, surviving by clerking books at Brentano’s and pilfering loose change, then she must be all right. Conni ended Ricardo’s clerking career. One night at the cash register another light-fingered clerk was nearly caught in a bad scene. Ricardo was shaken by the wild shouting and accusations of his friend’s close call. “So,” Conni had said, “quit. We can manage.”

“I’m not into celebrities,” Ricardo told a New York Times reviewer asking about Princess Di, Tennessee Williams, Sam Shepard, Jack Nicholson. “Liza with a zero,” Ricardo interjected. About the sundry rich and volatile who sat for portraits through his Hasselblad, he smirked, “I’m into people.” Nothing wrong for a Puerto Rican-Jewish kid, reared as a child of divorce in Brooklyn, to prefer his people in a certain charmed circle. Ricardo first made it into Manhattan when he was sixteen.

“Did you ever go to Max’s Kansas City?” he asked. “Did you ever have to go to Max’s Kansas City?” We conversed in taxis and cafes. “I went there every night for a year. I had to. The people I needed to meet went there. I met them. They introduced me to their friends.”

Ricardo toyed with the rich and famous as much as they amused themselves with him. One evening at a gallery opening, a wealthy and handsome patron walked up to Ricardo and said, “I’m looking for someone to spoil.” Ricardo said, “You’ve found him.” For the next four years they gave each other what they needed. At supper in a corner table at Paper Moon, the patron smiled at me and reached across the table, greeting Ricardo on his return with me from San Francisco, and dropping into his hand a brilliant diamond ring. Nice.

Whenever I pissed in Ricardo’s toilet, he looked down, insouciant, from the framed portrait Scavullo shot in 1974. Francesco caught him, hands jammed into his leather jeans, cigarette hanging from his mouth, torn T-shirt ight around his drug-lean torso, his Road Warrior hair tousled satyr-like. Once, much later, he wrote me a letter confessing that his main enjoyment in sex was uncovering the devil in his partner. I should have been more careful with this photographer who worked with light and shadow. Lucifer, the archangelic light bearer, was, at least, an angel flying too close to the ground.

“This is,” I told Ricardo, “your first incarnation in three thousand years.”

“How so?”

“I intuit it,” I said. “I get reincarnational readings off some people.”

“I’m one of them?”

“My wonder is why you waited so long between incarnations.”

The world and Ricardo were on no uncertain terms with each other. In this incarnation, or in past goat-footed Dionysian lives, Ricardo demanded, managed, and delivered what he wanted. Ricardo will, when his next death-passage is appropriate, take his life with the same hands with which he has created and crafted it. He will neatly, stylishly even, finish it. Ricardo is as close a mirror to my Gemini psyche as I have ever recognized. Fucking with him was very much fucking with his total being. Fucking with him was like fucking with myself.

Ricardo always wore black leather, even to the restaurant bar Paper Moon, where in the thin March afternoon sun, we brunched and talked and drank coffee and Perrier. People waved to Ricardo in New York, hoping he would nod back, the way people acknowledged me in San Francisco. His shows grew increasingly chic. Galleries across the country wanted to be the first on their block to showcase his talent that stripped the familiar masks from famous faces and transformed them. Ricardo’s talent was that he created psychic portraits; he was not one of photography’s army of motor-driven hacks. His insightful work was selling at a stylish clip.

The faces he chose, he chose judiciously, refusing to photograph anyone unappealing to his eye. Except for princesses. Princesses found great favor with Ricardo. Princesses called him early in the morning while we lay wrapped together, slugabed, his body tucked like a furnace around the curve of my back. “Hi, Princess.” He chatted on. His body heat melted me to cold sweats. His leather pockets held small plastic bags into which he dipped his finger, sticking it up my nose and his tongue down my throat.

“When we make love,” he said, “I want it to get to where it could go anywhere. I’m not as much into physiques as you are. I like to fuck with minds.”

“I like big arms, big pecs, and sensitive tits.”

“Nobody can work out and have a mind.”

“You liked Arnold.”

“Arnold was cute. He sat with all his clothes on and talked. He’s nice. He’s bright. He’s straight. The gay bodybuilders I’ve been with are so big they’re like fucks from outer space. I can’t relate to all that mass. It overshadows personality. I don’t like impersonal sex.”

“That’s a contradiction in terms,” I said. “If it’s sex, it’s not impersonal. Sex is always personal. Just because you don’t know somebody’s last name…”

“Aw, Mickey, you don’t actually believe that. There’s sex with somebody, and there’s sex with someone’s body.”

“You mean,” I said, “that sex is mainly prepositions. Some people you have sex with. Others, like bodybuilders who don’t move very well in bed, you have sex on. Some guys are so masochistically bottom, you have sex over. And others are so sado-aggressive, you have sex under.

“Stop,” he said. “Never get a writer stoned.”

It was six a.m. in a Westside diner. Ricardo pulled my rubber-booted foot onto the booth next to his leather thigh. We had spent the night sleazing through the Mineshaft orgy palace. We were both at the dawn end of a Saturday-night stone.

“Guess who got turned away at the Mineshaft last night,” he said. “Mick Jagger. “

“Why?”

“He showed up with a girl.”

“Let’s don’t go to bed this morning. What can we do on Sunday in New York? My flight isn’t until six.”

“I want to stop by Jack McNenny’s shop to check on flowers.” He pushed his corned-beef hash away. He ate very little, pouring instead orange juice into his alabaster body. He was very pale with light rose color in his cheeks and blue veins under his paper-thin skin, and, omigod, in that Sunday morning spring sun, I wanted to love him and wanted him to love me. “I have to drop some flowers off personally. Uptown. You come with me,” he said. “It’s business, but why not? From this one uptown gallery alone last year, I made over nine thousand dollars. I spend it all collecting things. Not the least of which,” he shook my boot, “is you.”

“Bullpucky flattery.” I changed the subject. “Your art show with Conni Cosmique is in June?”

“Conni deserves to be a legend. I photographed her from the start.”

His lens had given him frozen images of her. Through his camera he recorded the time lapse dissolves of their friendship. Jesus. I, at thirty-eight, looking like what a thirty-eight-year-old man should look like, sat across from him, at thirty-one, looking like a faunchild. What were the dissolves of our relationship? I was old enough to be connected with the tradition of erotic words. He was young enough to be the essence of photographed rock‘n’roll. Our differences fit: words and pictures.

“We need to get more done on our book,” he said. “That is if we ever get down to it.” He stubbed out his cigarette. “It’s got to be commercial and handled through a private source. A publishing house will rip us off.”

“My text will be less censored than your sex-and-fetish photographs.”

The Greek boy waiting on us asked, “Separate checks?” Then he glanced at Ricardo squeezing my rubber-booted foot in his crotch between his thighs, and then at our hands held across the table. A true Greek, he answered his own question. “One check,” he said.

“Your photographs need to be more suggestive than literal. Instead of a handballing shot of penetration…”

“…We need a nice ass shot with a can of Crisco sitting next to a fist rising up in the foreground.”

“A sexual still life,” I said. “Let the viewer’s mind mix the three elements. “

He changed the subject. I wasn’t supposed to talk about his work. “Why don’t you stay through tomorrow night? Warhol’s giving an Academy Awards party at Studio 54.”

“My boss expects me back. The printer is returning the blueline for our next issue tomorrow.”

“Come on, stay. That leather rag you write can live without you one more day.” He twisted my boot. “Come on, stay.”

“Don’t, Ricardo.” I pulled my boot away.

He held my hand in place on the table top.

“You know,” I said, “it embarrasses me that I have to work. At a job-job, I mean. I’ve never had to work before. Teaching wasn’t work. Teaching was a labor of love, around the clock seven days a week, always with papers to grade, living with lofty responsibility, and, shit, it never mattered if everything went down the tubes of those thankless lectures. Did all those words evaporate as soon as I spoke them, or did some of them actually lodge forever in some of my students’ heads? I mean, now, working from eight-to-five embarrasses me. Especially in front of you. I’m a writer hired to hack it out for A Man’s Man. Wouldn’t Thoreau be really pissed? You, on the other hand, work so very effortlessly.”

The afternoon before, Ricardo had sat me down in his SOHO studio. The sun slanted through his loft windows, across my face, and hurt my eyes.

“You okay?” He unscrewed the legs of his tripod.

“Yeah.”

“Come on, Mickey. You’re lying.”

“How embarrassed do you want me?” Why did the sonuvabitch always have to press the tender nerve. “I don’t know why.”

But I knew why. Ricardo’s eye was true. His camera-eye was truer. I finally understood why Indians feared the soul-revealing, soul-stealing devil lens. We both played at being cynics abroad in the world; maybe he wasn’t playing; maybe mine was only attitude; maybe his was real. His sight and insight cut through bullshit. In conversations, we threw snide asides to one another. His honeygreen eyes worked overtime. The first night we made love, his tongue licked repeatedly across my eyeball. That was a probing first. No one had ever so directly fucked my sight. Sitting in his sunny studio, I feared his eye, malocchio, his evil eye, his wonderful eye that through the added eye of his lens might see me suddenly different, might see not my appearance but my reality. I had seen others whose faces he had photographed. In real life they seemed so much less than the reality he froze into the single frame. I did not want to be diminished. I wanted to be transformed. My fear of his camera was primitive.

Cameras, after all, are the guns of our time. Hadn’t Harvey Milk, as it turned out with high irony, owned a Castro camera shop? Yet I wanted Ricardo to see through his Hasselblad what he wanted to see of me. I feared him seeing me harboring resistance to his art. My right eyebrow in photographs too often rises up in arch opposition to the process that tries to capture a whole person in a single frame.

Yet I wanted to give the devil his due. I wanted him to have his way with my face. With me. I wanted to give way to him because I can never give way to anyone. I cannot submit to a man I cannot respect. I wanted to give Ricardo the surrender he wanted from me. I wanted to give Ricardo the sweet, sweet surrender I needed to give somebody just once in a lifetime. I feared he might slip in the shooting. I feared he might somehow fail to transform me, because of my resistance, reluctance, recalcitrance, because of my arched eyebrow, into the portrait he desired.

In fact, he shot me effortlessly and quickly. He sealed the roll of film and handed it to his assistant working in the darkroom at the rear of his loft.

“The contact proofs will be ready tomorrow,” He said. He hugged me.

I made us instant coffee in the kitchen while he rolled joints in the living room. “Something’s burning,” I called. “Have you lit something?”

He came out to me in the small, jumbled kitchen. Under a silkscreened icon of Jackie Kennedy veiled in multiple-image mourning, an ashtray broke from smoulder to blaze on the table littered with Con Edison receipts and letters from galleries. Ricardo brushed the small fire to the floor and stomped the flames with his black point-toed cowboy boots. Minor disasters stalked us: insane Saturday night kamikaze rides up the Avenue of the Americas; a young gayman shot in the shin by a mugger in the lobby of a Charlton Street apartment building; a naked man falling out of a piss-filled bathtub to the concrete floor of the Mineshaft. Ricardo laughed. “You’re paranoid,” he said.

“Signs and omens are everywhere.”

“I read that homosexuality can cause paranoia.”

“Homosexuals have real reason to be paranoid.”

He lowered his eyes. His mouth grew thin, tighter. Ricardo resented resistance. Ricardo loved congenial compliance.

I made a thousand excuses that night trying not to go to bed with him. He was pissed, but in control. He deflected my bedless hints. I wanted to enjoy some neutral time together. He needed time to work his seduction. He suggested supper at Duff’s on Christopher Street. We lingered long. He plied beautifully subtle ways to untangle my none-too-ambivalent attitude. He led me the way a good dancer seduces his partner into bending to full dip. Ricardo, for some reason, wanted me, as me, with him, not in anyway forever, just particularly for that night of the afternoon he had shot me.

“This is my farewell tour to New York,” I said. “I’m joining a monastery. This is it for sex. I’m tired of life in the fast lane. I’m getting born again.”

“Mickey, come on. Yeah. Sure.”

“I mean it, Ricardo. I’m tired of fistfuckers and dirty people. I’m tired of everybody always being sick with hepatitis and amoebiasis and clap and crabs and you name it. Our lives are a constant search for new ways to be disgusting.”

“Look at your eyes.”

“What do you mean?”

“You’re dirty, Mickey. I knew you were into hard sex. You have a face that could have been drawn by Rex. I could tell you were dirty by your eyes when I met you.”

“What about my eyes?”

“You’ve got dark circles.”

“I won’t in two weeks. I’m not kidding. I’m heading back to California, I’m doing my own version of being born again. I don’t want my face to look like a collapsed cake baked at too high an altitude.”

“Dark circles are what I look for. Interesting people have dark circles.”

“Ricardo Rosenbloom’s famous raccoon-effect.”

“So you’ll never have sex again. You’ll just think about it. Just write about it for that monthly rag you work for. Just jerk off thinking about it.”

“Hard sex leads to hard times. None of us ever thought that Gay Liberation would end up in Intensive Care.”

“You need hard sex.”

“I’ll settle for soft.”

“You shouldn’t spread yourself around so much.”

“I’ve always wanted to see everything that was going on. As a writer I have to. I never meant to turn into the Wife of Bath.”

“You should do it with one person. With me. Not with every man at the Mineshaft. You should have come home with me the nights you’ve been here.”

“I couldn’t.”

“Come on, Mickey. What do you mean, you couldn’t?”

“I mean, I could, but I didn’t want to.”

“Didn’t want to what?”

“Didn’t want to have hard sex, which is what we always have. I really only wanted to see what was going on. I never spread myself around. I didn’t want to get dirty. Not even when I got dirty. There’s been a madness on us all for some time.”

“There’s no madness. What is, is. And the fact is, Mickey, deep down in your secret soul you’re dirty, nasty, filthy.”

The green glass lampshades in Duff’s lit pools of light over separate tables. The waiter offered to fill our coffee cups yet another time. Ricardo waved him off. I waved him on. He stopped. Ricardo and I reversed waves. We laughed.

“Let’s just pay the check,” Ricardo said.

We spread our cash across the brown table under the green light and pulled on our leather jackets.

“Born again?” he asked.

“Born again,” I said.

What a half-breed! He smiled his best Puerto Rican smile, and nodded that all-knowing, seductive Jewish look he transmitted so easily with his eyes. He held out his tongue, peered narrowly at me, and shook his head yes. “You’re dirty, Mickey.”

At the door, the cold spring night chilled straight through our leather jackets. Ricardo headed out onto the crowded midnight sidewalk. A couple hundred guys cruised up and down Christopher from Ty’s bar to Boots and Saddles. I always walked faster than anybody I ever dated, but Ricardo always walked faster than I.

Knowing full well we were headed toward disaster, I followed his fast pace down to Sheridan Square. The showdown was coming right on cue. His arm almost raised to hail a taxi. I blocked his view of the oncoming traffic. It was midnight on March 31. A little after.

“Well, Red Ryder,” I said. “Where we goin’?”

He looked at me. His pale skin flushed with the cold.

“I have to go home,” I said. “I have a lot of work tomorrow.”

Into his eyes came that look I’ve see so often in other men’s eyes when finally I, so much a conciliatory Gemini, reverse, and tell them, somehow for the first time, I have a will of my own.

“I’m a very disciplined person,” I said, “too disciplined with Catholic guilt, and since I’ve known you, I’ve traded writing for fucking. I’ve preferred to spend time with you.”

He eyed me, impatient as a coiled serpent, listening.

“Since we’ve met, I’ve taken the luxury, yeah, the luxury, of spending time with you. My drug intake has gone up a hundred percent. You tell me you want to use fewer drugs and have a wider range of sex.” I pulled my collar tighter around my neck. “I can’t range any further into the kind of sex you want unless we take more drugs. And I won’t. I can’t. I refuse. Look at you, these last weeks you’ve produced minimally. I’m not producing at all. We’ve fallen into the bad habits of those gayboys I hate to see wasting their time cruising each other on the corner of 18th and Castro.”

“Maybe we both need this interlude, this time-out together,” he said.

“For what? To develop our next creative stages? To write the book we’ll never write?”

“You live it up to write it down.”

“Yeah. Sure. This is what’s left of Thursday. Monday, when I’m back in San Francisco and you’re here, I’ll have to write up a report of what I did and publish it in the next issue.”

“Listen, Mickey, if you want to do anything, you can. You do.”

“If we go back to your place, we’ll have sex. We’ll be up late. We’ll wake up late. We’ll have sex again. I won’t do what I must do to survive. Fuck it, man, I’m supposed to be here on business.”

We stood a long time in absolute silence, stoned on grass, in a myriad of lights and traffic. Finally, Ricardo, staring into mid-distance, said, “It’s stupid.”

“Everything is.”

“It’s stupid.” He wasn’t even holding one of his usual Marlboros to punctuate his gesture. “I’m not in love with you.”

Oh God. The subject is up. He brought the unspoken up. Oh Jesus.

“But when two intelligent people make excellent love, if they don’t do it when they can, it’s stupid.”

“If we did it tonight, it wouldn’t be good.”

“You should have rested up last night.”

“I only came once. I cum more than that everyday. Cuming isn’t the point. I’m on vacation. You’re not. I’m embarrassed. I work at a silly-ass job-job. I don’t want to work. This year my vacation is only six days. So I should have stayed in last night?”

“It’s all stupid.”

We grew cold standing on the curb. Hidden dumps of frozen snow stood unmelted in dirty alleys around the corner. He tried to be so reasonable.

People milled around us. Bits of conversation froze like cartoon balloons in the air: “Nobody cares about the other guy, ya know?” New York was on the eve of another transit strike. A man, pissed off in general, and not expecting us to answer, sort of asked the crowd waiting to cross with the light: “Can anybody tell me how to get to Greenwich Street, or should I just go fuck myself?”

“Let’s get a taxi,” Ricardo said.

“For which way?”

“I’ll drop you off.”

“Don’t commit yourself to a direction,” I said. “Maybe you ought to go out too.”

Ricardo waved a taxi over and climbed in. I followed. We sat far apart.

“Charlton and Sixth.” I said.

We rode silently. No hands on each others’ knees now. Where was that curious dyke photographer? Earlier that day she had wanted to shoot us together when she discovered us sitting in Stompers Gallery and Boot Shop. She was doing a book on gay couples and she liked the way our arms and legs twined so well around each other.

She was right. Our bodies were a perfect fit.

Ricardo held his honey-green gaze straight ahead.

The cab turned the corner. I fished out five bucks and held the money folded in my hand. When the cab stopped, I pushed the bills between Ricardo’s clenched fist and his leather-chapped thigh. I turned full face to him, and the perfect rhythm of my words spilled out: “What you said you’re not, I think I partly am.” I meant “in love.” I climbed out, closed the door, and walked off without looking back.

New York, New York. Alone again. Naturally. And I wasn’t even looking to be in love. Maybe I didn’t want him. Maybe more than him, I wanted the idea of him. The ideal of him. I was cold walking back to the 2 Charlton Street apartment where I was crashing near Jack McNenny’s flower shop. Unlike Lot’s wife, I didn’t, wouldn’t, couldn’t look back. Exits, by then, I knew how to make, by heart. No one’s ever left me; I’ve always left them. Sort of.

Ricardo Rosenbloom was excellent stuff.

Two mornings later, on the Sunday after Easter, lying again with Ricardo in his loft, I felt his arm wrap around my neck.

“What I said the other night,” he whispered, “I didn’t mean.”

I kissed his long artist’s fingers. I said nothing. No need to.

Later that morning Ricardo was to meet me for brunch before my flight. Instead, as I finished packing, he phoned from Paper Moon. His interview with The Times was running over. Somehow our relationship perversely thrived on such ellipses. Again, we were to have no dramatic farewell scene. Two months before, when he had come to my Victorian flat in San Francisco on magazine business, and stayed six weeks to make love, I had bought a fast-lane ticket and accompanied him back to New York rather than say goodbye. We gained another ten days. But now, this Sunday, no final kiss before jetting back.

“I wanted to get really crazy. I wanted to go so far with you,” he said over the phone.

“I didn’t know we had a deadline.”

Were our ships in convoy for two months never to connect again? If so, then what-was must remain always so dear to my heart and my head. We rarely dared say “love.” We had no need. Life is a series of beautiful gestures: a look, a lick, a touch, a word, sex verging on love — each and all enough.

We were parting again.

I stood at the phone near my backpack. He stood in a booth at Paper Moon with clever people waiting to spoil him more.

“Thank you, Mickey,” he said.

“Thank you, Ricardo. Caro Ricardo.”

A taxi took me through heavy Sunday traffic to the East Side Airline Terminal. On the radio the BeeGee’s were insistent on “Stayin’ Alive.” A Carey Airporter Bus drove so slowly through the bumper-to-bumper cars to JFK that once it was halfway into the airport drive, I jumped the bus, begged and bribed a taxi driver to get me through the jam to the United Terminal. He balked, refused, until an airport taxi manager forced him to take my fare. He drove so reluctantly, I exited the taxi in heavy-stalled traffic, and ran two hundred yards in a headwind, juggling my backpack, a book from Ricardo, and a large photograph of Conni Cosmique drymounted on posterboard. The wind and exhaust blowing through the dirty brown grass caught the photo like a ship’s sail. I pulled Conni like a lover to my chest.

“No luggage to check?” the ticket agent asked. “Go to the head of the security line or you’ll miss your flight.”

I ran, heart pounding, through the terminal, newspaper wrapping shredding off Conni’s huge photograph, past curious travelers killing time, past phone booths where I had planned to page Ricardo at Paper Moon, down the ramp, into the plane, into my seat.

“I want, I need, I love, yes, love, with incredible respect, this man Ricardo Rosenbloom,” I wrote at 25,000 feet in my journal, “even though we may never really for long times be in the same city or country. He travels to castles with princesses, after all. By day, I job-job. By night, I write.”

“I’ll send you a print of your photograph,” he had said from Paper Moon. “It’s quite good actually.”

I wanted to see. I almost couldn’t wait, I wanted to say, to see what vision this sophisticated photographer had found in me. I liked, as Ricardo would say, all the “takes” he had on reality. I wanted to see his “take” on me. I had to see if I looked dirty: not from the inside out — that I had always known — but from the outside in. I had to know if I had a gay face: the haunted, hunted, distorted kind. I had to find out if my face had become like the Fellini faces in the bars and the baths: a dead give-away of whatever it was that made us all different from other men.

Through the torn newspaper wrap, Ricardo’s shot of Conni Cosmique’s enormous face stared at me with one inquiring eye.

Two months in a life is not much. Two months in a year is considerable. Maybe we were too hot not to cool down. My affairettes usually run the wash-tumble-and-hang-it-up cycle. Whose don’t? But this time something special passed between us. Revelation. Reflection. Lust. Darkness and light. Good and evil. Maybe even love. That’s the value of even impersonal ships passing in the night: reassurance that in the night sea-swells other lights, rising and falling, loom closer out of the distance, and for a brief passage, a single man, borne back against the current, is not forever alone.

* * * *

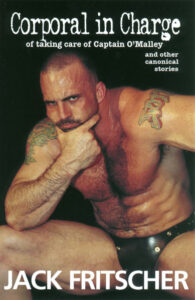

“Caro Ricardo” was written in 1979 as a fictitious homage protecting the privacy of Robert Mapplethorpe — who so loved this story he asked me to write — that just before his death he handed the typed manuscript to his chosen biographer and said, “This story is about me.” Ten years later, this fictitious story built on my 1978 article “Mapplethorpe Censored” in Son of Drummer became the basis of my factual Mapplethorpe obituary published in Drummer 133, September 1989, which in turn became the basis for the 1994 book memoir, Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera.