Chapter also available in PDF

HEADLINE NEWS:

Stonewall Riot Ends Prehistoric Gay Period,

Begins LGBT Civil Rights Movement…

Suddenly That Summer

1969

What It Was Like to Be Gay and Alive

That May and June

Mark Hemry, Editor

“At Stonewall, gay character changed.”

— Jack Fritscher, Gay San Francisco

Do you remember where you were during Stonewall? Are you younger than Stonewall? Half a century ago, Stonewall grew out of our larger American struggle for civil rights in the 1960s during the sexual revolution sweeping the world. “Stonewall” was happening everywhere before the June 1969 riot broke out at 63 Christopher Street. On April 23, 1961, a crowd of gay men’s voices was recorded for the first time cheering uncloseted on the live-concert album of Judy at Carnegie Hall. On the West Coast, queens stood up against the cops in Los Angeles at Cooper’s Doughnuts (1959), and in San Francisco at the Why Not? bar (1960) and Compton’s Cafeteria (1966).

Almost five years to the day before Stonewall, the June 26, 1964 issue of Life magazine documented San Francisco’s gay bar, the Tool Box. Jack Fritscher wrote in Drummer magazine, “That Life article was like an engraved invitation to queers everywhere to come out of the closet and immigrate to major cities where there was strength in numbers.” Life threw down a gauntlet: “A secret world grows open and bolder. Society is forced to look at it—and try to understand it.”

Against the odds of straight history, the Stonewall Rebellion of June 28, 1969, became the epicenter of a Queer Culture Quake that ended our “Last Prehistoric Gay Period.” At Stonewall, we showed our true rainbow colors. After a week of riots the media could no longer ignore, the New York Daily News headlined on July 6, 1969: “Homo Nest Raided, Queen Bees Are Stinging Mad.” Ouch!

Jack Fritscher was not in Sheridan Square at the Stonewall rebellion, but he was professionally prepared to be an eyewitness to the media coinage and coverage of the events. At eighty, he is the San Francisco writer, storyteller, and historian whose sixty-year career predates Stonewall itself. Published as a teenager in national magazines in 1957, he wrote the first doctoral dissertation on Tennessee Williams in 1966, and as a university professor began writing gay fiction and reviews about gay popular culture in 1967.

In his essay “Homomasculinity: Framing the Key Words of Gay Popular Culture,” he wrote: “Reporting the Stonewall uprising six hours after the first stone was cast, a reticent New York Times in ten short-shrift paragraphs used the words homosexual once and young men twice. The New York Post in five paragraphs used homosexual only once but actually dared quote the framing chant of gay power. In its Independence Day issue (July 3, 1969), the Village Voice nailed the gay gravitas with the headline feature ‘Gay Power Comes to Sheridan Square.’ On November 5, activists successfully picketed the Los Angeles Times for refusing to print the word homosexual in advertisements. By June 1970, thousands of gay militants—veterans of the civil rights, women’s lib, and peace movements—marched past news cameras with signs reading ‘Gay Pride’ and ‘Gay Power’ at the first Christopher Street Liberation Day in Central Park.”

“So how,” he asked, “did a routine NYPD raid on a Mafia-owned gay bar in Greenwich Village morph from a bar fight into a symbol for the gay civil rights movement in much the same way that the march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, on March 7, 1965, became an impelling roots moment for the black civil rights movement?”

“Even though Stonewall wasn’t the first rebel act in the gay war of independence,” he wrote, “it scored the best news coverage to date. In the twenty-four months after the Stonewall riot, it was activist journalists thinking and writing about the shifting paradigm in gay social justice who did the pre-historical math, created the origin myth, and framed the importance of its commemoration in order to organize the screams, bottles, and bricks into the rally cry of resistance and enlightenment inherent in the Realpolitik of the Stonewall rebellion.”

Assessing writers working inside gay culture before, during, and after the happening of Stonewall, Willie Walker, founder of the GLBT Historical Society of San Francisco said, “Jack Fritscher, a prolific writer who since the late 1960s has helped document the gay world and the changes it has undergone.” Before Stonewall, Fritscher had written a dozen published short stories and his first novels What They Did to the Kid: Confessions of an Altar Boy (1965) and Leather Blues (1969), as well as his dissertation Love and Death in Tennessee Williams, and his 1969 review of The Boys in the Band for the Journal of Popular Culture (January 1970). And he was already journalizing the text that became his novel Some Dance to Remember: A Memoir-Novel of San Francisco 1970-1982. In February 1969 he had begun researching his nonfiction book Popular Witchcraft (1972). In a signature eyewitness way, Fritscher’s fiction and nonfiction connect Stonewall and Castro Street.

In Gay San Francisco, he recorded his participation in civil rights with Saul Alinsky in 1962 on the South Side of Chicago, and at the August 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago when hippies and yippies and gays, including Allen Ginsberg and Jean Genet, fought in the streets against the Chicago cops clubbing the surging convention crowds who chanted in self-defense to the live TV cameras, “The whole world is watching.” He wrote, “You don’t have to be Rosa Parks to figure that the people’s resistance against the cops at the Democratic Convention in Chicago 1968 was a precise model and encouragement ten months later for the queens’ rebellion against the cops at the Stonewall Inn. Without Chicago, Stonewall may not have happened.”

The spring of 1969 was a wild time in the Swinging Sixties. On June 9, 1969, eighteen days before Stonewall, gays thoughout the world hosted parties celebrating 6/9/69. On June 20, 1969, seven days before Stonewall, Fritscher, an openly gay professor teaching at university since 1964, turned thirty. He was a constant observer in his journals of the gay push forward in the revolutionary 1960s. Four weeks before his birthday, he had returned from Europe where “in Holland a wild sexy Dutch boy” had recruited him “into a student takeover of the University of Amsterdam.” The excitement of that rebel melee swept him further to La Rive Gauche in gay Paree. He wrote: “Paris still vibed ‘red’ with a peoples’ revolutionary brilliance that May 1969 after the riotous Prague Spring of 1968 when student strikes had shut down old-style Paris and post-war Europe. The most popular music worldwide on jukeboxes in gay bars was the explicit pair of whispered duets by Serge Gainsbourg and his pop goddess Jane Birkin anointing 1969 sexually in their shocking ‘69 Annee Erotique’ and ‘Je t’aime, moi non plus.’ Oh, mon amour!”

About Paris in 1969 in the 5th arrondissement, Fritscher wrote about the “gay wave” sweeping western culture: “the bedroom windows reached from floor to ceiling,” and he “…fell in, and out, of springtime love, and the Dutch lad shapeshifted one night at Le Keller’s bar near the Bastille into a young Brit whose leather-biker good looks swept us both across the Channel to London which was suddenly that summer way more queer than the straight scene of the Beatles and Carnaby Street because of the decriminalization of homosexuality in 1967. Our gay London was the leathery Coleherne pub in Earls Court, the cruisy movie theaters in Piccadilly, the squaddies of Studio Royale, the nighttime sex in the wild woods on Hampstead Heath, and the steaming pleasures of the ancient Turkish baths tucked under York Hall on Old Ford Road. Those Victorian working-man’s tubs, next door to the Museum of Childhood, were perfectly situated for a little extra cottage sex in the busy, dank public toilet outside the Bethnal Green tube station. And from London, the amazing gay wave rolled on to New York and the Rambles in Central Park, the Off-Broadway Boys in the Band, the Everard Baths, the afterglow of the 1966 Mattachine Sip-In at Julius’ swellegant bar, dirty 42nd Street bookstores, Fire Island, Bernadette Peters in Dames at Sea, Warhol at the 55th Street Cinema, leather bars, the Ninth Circle, and the counter-culture of the Village. During that erotic spring just before that dramatic summer’s Stonewall and Woodstock and Moon Landing and Manson murders, gay novelist James Leo Herlihy and gay director John Schlesinger turned Midnight Cowboy from a conventional buddy movie into a complex male love story that won the Oscar for best picture. And lots of us gay men shouted ‘Bugatti!’ as we fell in love with the divine Vanessa Redgrave dancing as the divine Isadora Duncan in Cinemascope, naked and wrapped in the star-and-sickle of the red Soviet flag, fucking handsome young Russian Communist poets and revolutionaries. The underground gay world of the Swinging Sixties was an on-going worldwide orgy long before Stonewall turned sex political.”

Two days after his thirtieth birthday, and five days before Stonewall, he felt “the sorrow most gay men suffered when Judy Garland accidentally overdosed, age 47, in her home in London on June 22, 1969.” He wrote, “As thousands of grieving gay men queued up in Manhattan to stream past her laid out like a queen in an open coffin during her all-night wake at Campbell’s Funeral Home on Madison Avenue, June 26 turned into June 27. The mixed emotions and motivations hit a gay nerve and then exploded four miles south at the Stonewall Inn as June 27 became June 28. If Judy Garland, the ventriloquist of gay code, had not died,” he added, double-billing her with the Democratic Convention, “Stonewall may not have happened. Nowadays it’s a gay joke that if the mob of people who claim to be veterans of the Stonewall riot are not lying, the crowd would have been greater than the 400,000 who showed up six weeks later at Woodstock.”

*****

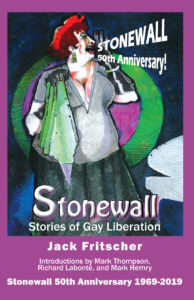

As Stonewall turns fifty and Fritscher turns eighty, I have with a curator’s sense of finality collected the original nine keepsake stories with the original introductions by Richard Labonté and the late Mark Thompson from the fortieth-anniversary edition. I have added a new version of “The Story Knife” along with a new tenth story, “Three Bears in a Tub,” finishing the anthology with a new essay, “Lost Photographs, Found Genders,” telling the backstory of how the one-act play, “Coming Attractions” came to be produced in 1976.

What might the LGBT world feel as Stonewall reaches middle age? Or old age? “Stonewall 50” deserves a huge celebration, and may perhaps, especially in our age of political resistance, initiate a true renaissance of LGBT culture that, even after Stonewall, has suffered so many years of oppression at the hands of fundamentalists. “Even as we gays disappear,” Fritscher wrote, “we reappear. Twenty-five years ago marking ‘Stonewall 25,’ hundreds of thousands of us appeared on June 26, 1994, marching in worldwide Pride parades to reappear as millions for ‘Stonewall 50.’”

“If in 2019,” Fritscher said, “one in ten people is gay on our globe, with a population of nearly seven billion, well, that’s inching close to one billion gay folk who are more linked, and therefore more powerful and able to create change, than the small crowd at Stonewall who succeeded beyond their wildest dreams when there was no Internet, no texting, no instant messaging, no viral call to action, no Facebook, and no video footage of the riots on Youtube. That small band of twentieth-century folks with analog voices, all of them, whoever they were, working with what they had, gave us at Stonewall a teaching moment about the on-going revolutionary responsibility we twenty-first-century folks with digital devices have to amplify and complete our liberation in our time of rising fascism if there is to be a ‘Stonewall 75’in 2044 and ‘Stonewall 100’ in 2069.”

For myself as editor striving to present information accurately, I must, in transparency as a longtime media producer, say that I have known Jack Fritscher intimately since the 1970s as his lover and as his domestic partner and as his spouse of forty years. As a reader, I’m also a fan which is why I think of this anthology of gay entertainment as a worthy project capturing the spirit of Stonewall. As actor Ian Richardson repeated so famously in the British series House of Cards, may I say, “You may very well think I have access to the author’s most intimate thoughts and private papers, but I couldn’t possibly comment.” As with the Woolfs and Bells in Bloomsbury, who better to be an eyewitness than a spouse sorting out how things went that-a-way behind a writer’s study door?

This Stonewall anthology surveys a fictive essence of Fritscher’s sixty-year career capturing the character, dialogue, nuance, arts, and ideas of the gay culture he loves. Guided by a veteran elder’s canonical sense of gaydar, he celebrates gay “drama,” diversity, and magical thinking in these ten tales scanning the curvature of the Queer Earth—from the 1906 earthquake in “Meet Me in San Francisco” through the camp-fest last hour before the NYPD raid in “Stonewall: June 27, 1969, 11 PM” on up to gay marriage in “Mrs. Dalloway Went That-A-Way.” The settings range from Christopher Street in Greenwich Village to a Midwest movie palace, and from an Alaska cruise ship to a Castro Street teeming with gay refugees from the American culture wars. His characters manage to survive, like Stonewall itself, against all odds.

Elaborating on the changes caused by Stonewall, and writing stories told with a humanist’s feel for the way we are, Fritscher uses an omniscient narrator’s voice to inflect his stories with humor, irony, and drama. He is a prose stylist who can turn a phrase with a flip that surprises and delights. His dialogue seems as lively on the page as it is in the plays and screenplays he has authored. The following thumbnails may reveal how some of his stories worked for me personally over the years, and professionally during the time my task was to select the stories for this “Stonewall 50” anthology.

The title tale “Stonewall: June 27, 1969, 11 PM” is a drag comedy with All About Eve dialogue that Will and Grace never dared try. True to Aristotle’s classic unities of time, place, and action, “Stonewall” unfolds in the precise “Last Prehistoric Gay Period,” the final sixty minutes leading up to the NYPD raid on the Stonewall Inn. It was encouraging to me that the first publisher of “Stonewall,” Thomas Long, editor of Harrington Gay Men’s Literary Quarterly, wrote: “Fritscher’s ‘Stonewall’ is pitch-perfect.” Flying the rainbow flag, these literary short stories bring Fritscher’s stylistic mix of humanism and eros to the gay literary canon. Two of the stories, “Stonewall: June 27, 1969, 11 PM” and “Chasing Danny Boy,” give me special delight in sharing. As entertainment, these stories reflect our evolving gay hearts and minds and illustrate Fritscher’s Woolfian observation: “At Stonewall, gay character changed.”

“Stonewall: June 27, 1969, 11 PM” with its comic “sixty-minute countdown,” camp-fest characters, “snap” dialogue, and homosurrealistic style, might very well be, as Advocate editor Mark Thompson said, “a nominee as one of the twentieth century’s best gay short stories.”

“Chasing Danny Boy” gayifies the Celtic mythology of the author’s own Irish roots, camping for craic on the Complete Irish Mythology of Lady Gregory with streaming bits of James Joyce. His four young millennial punks explore their polysexuality with sex, drugs, and rock in the underground world of Dublin during the last summer of the twentieth century. “Chasing Danny Boy” was first published as the title story in Chasing Danny Boy: Powerful Tales of Celtic Eros featuring “Last Rites” by Neil Jordan, director of The Crying Game.

“Meet Me in San Francisco” is a romantic Valentine of teen boys in love, separated in the deadly San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906 when 3,000 people died and eighty percent of the city was destroyed.

“The Unseen Hand in the Lavender Light” is an existential profile of a movie-mad young gay boy abandoned during World War II by his waitress-mother at the Bee Hive café. Disoriented and confused, he comes out in a dark movie theater where, lit only by the light of the projector, he survives as an usher, and tries to make something of himself as the conformist 1950s of corporate Hollywood movies evolve into the swinging 1960s of personal underground cinema.

“The Barber of 18th and Castro” features two characters locked in one’s struggle to come out. This black comedy about sex worship dramatizes how gay pop-culture photography in “physique” magazines drives the coming-out process. Think Alfred Hitchcock directing a psychological thriller about existential fear and erotic fantasy on Castro Street in 1973, four years after Stonewall.

“The Story Knife,” noted historically by Men on Men editor George Stambolian, is the shipboard rom-com of a redheaded Irish-Catholic priest who as an ordinary guy struggling in an age of AIDS discovers that temptation has turned him into a sex-tourist beguiled by a cabin boy from Genoa; so what does he do with his new video camera? The new pentimento version in this edition has been re-imagined cinematically by the author from the 2009 edition.

“Mrs. Dalloway Went That-A-Way” is a touching vernacular story of gay marriage, eldercare, rising matriarchy, and failing patriarchy in the last summer of the millennium. The narrative helix, delicately wrapped around a gay man’s mother, Princess Diana, and the film version of Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, teases out a tender gay love story as appropriate as Michael Cunningham’s Woolf homage, The Hours.

“Three Bears in a Tub” is a breathless one-sentence comedy of a summer evening on a lake in the Ozarks when three good ol’ boys in a rowboat mix and match under the full moon and find family in each other.

“Sweet Embraceable You” is a comedy about two couples—two women and two men—in the first days of gay gentrification on Castro Street surrounded by people self-fashioning new gay identities in the wonderful 1970s window between penicillin and plague.

“Coming Attractions: Kweenasheba,” the stage adaptation of “Sweet Embraceable You,” is the author’s 1976 one-act play produced by the Society for Individual Rights (SIR) for San Francisco’s Yonkers Production Company

“Lost Photographs, Found Genders” is the author’s history of the social changes around the San Francisco production of his play, “Coming Attractions.”

Mark Hemry

San Francisco 2019